He recalls a tragic era that formed the background of his identity as a Kazakh and a Soviet citizen. Nor does he seek to condemn the Communists who presided over what must be the first major case of ethnic cleansing recorded in the 20th century. In fact, we know that he himself worked for years as a faithful defender of he Soviet Union, including a heroic stint on the war front after the Nazi invasion of the USSR. Sheikh-Ahmadov is not offering another anti-Soviet tract.

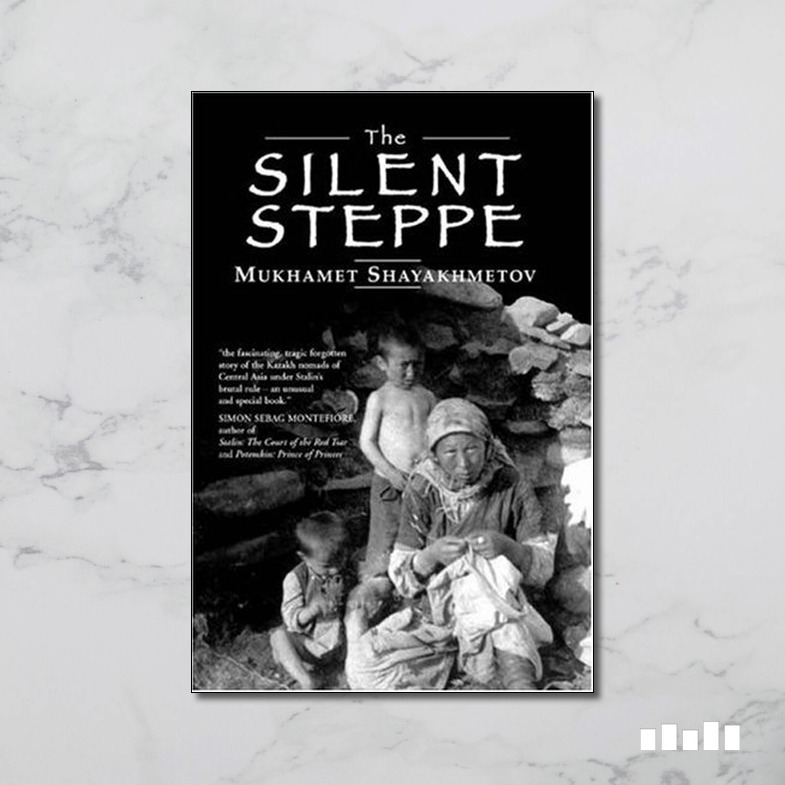

It is the story of that conflict that Mukhamet Shayakhmetov (Muhammad Sheikh Ahmadov) narrates in this strange book that, despite, or perhaps because of, its cold and detached tone, could easily break your heart. His Bolshevik Revolution carried a messianic message for the whole of mankind the Red Dawn was to spread to every part of the globe, starting with the territories controlled by the fallen tsar.

Now that the Tsarist yoke was lifted, they wanted to be free to organize their societies in accordance with their own values and aspirations. They did not want to change, even if that meant a better material life for them. The overwhelming majority of Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbek and other Turkic nations plus the Persian-speaking Tajiks and Sarts were deeply attached their traditional faiths and cultures. On the ground, however, a different reality would not permit the Bolsheviks to play the role of saviours.

The Tajik Sadruddin Ayini, the Uzbek Ahmad Danesh, and the Karaklpaq Abdul-Rauf Fitrat had welcomed the October Revolution as the dawn of liberty and progress for Muslims throughout Central Asia and the Kazakh steppes. Originally, that simplistic view had been peddled by a handful of Muslim intellectuals who had become acquainted with Marxism during their studies in Moscow or Petrograd, the present-day St. At the end of the hour, he had decided that the nations in question were suffering under “feudalism” and had to be rescued by the Bolsheviks, and brought into the modern world, kicking and screaming. Thus he devoted an hour to deciding what to do about the Turkic Muslim nations who lived in the southern and steppes of Russia and throughout Central Asia. The Bolshevik leader had never visited those areas, knew nothing about the people who lived there, and had virtually no contacts in what was an entirely different world.Īs always, Lenin looked for simple formulae to explain complex situations that he did not have enough patience to study in depth. Sometime during the Russian Civil war of 1918-21, Lenin, having established his control over Petrograd and Moscow, began to address what he termed “the problem of indigenous people” in the outer reaches of the crumbling Tsarist Empire.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)